On Seeing: A Journal – #256

May 22, 2018

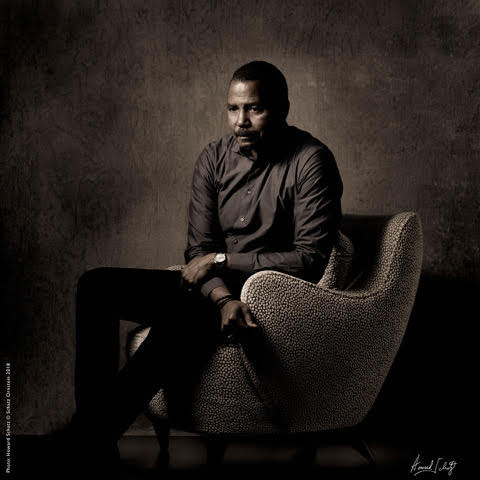

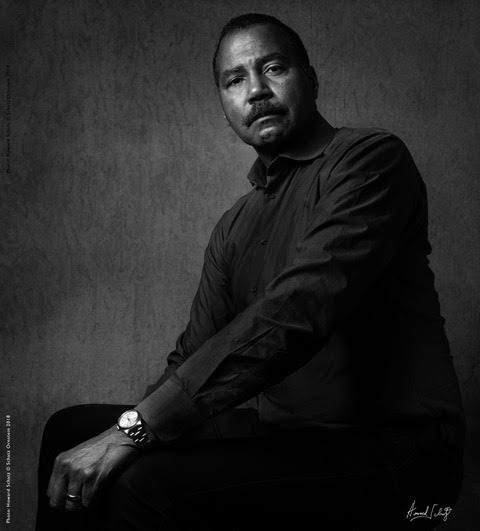

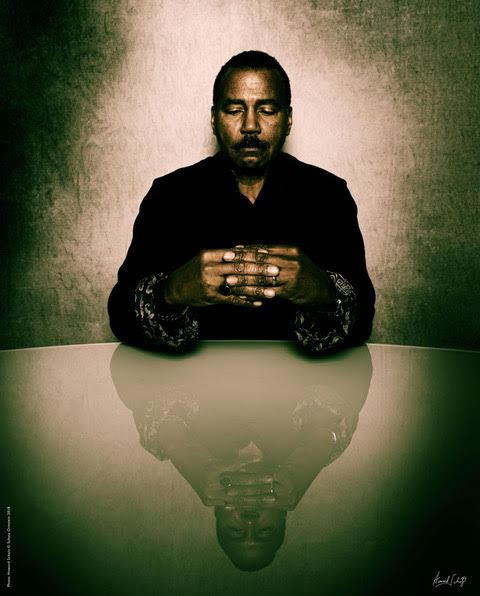

Before discussing the work of the eminent journalist Bill Whitaker and presenting our interview, I want to explain my use of more than one portrait for the majority of individuals in my new project ABOVE & BEYOND.

I work hard to create photographs of people, whether famous or not, that go beyond interesting or even very good. The truth is – and it can be a hard truth for any photographer to admit – that just about anyone can learn to make a “good” portrait. Making a remarkable one is hugely challenging.

In my current project I am using the images I make of each extraordinary sitter as raw material—I have a vision, a preconception, and shoot (capture) such imagery with a final idea in mind. In the days that follow, sitting at my computer, in my “digital darkroom” I work on the images. In old darkroom terms, I’m burning and dodging, making double exposures, layering the images, etc., all in an attempt to create images that are original, that I hope will say something meaningful and will give viewers something to study. Often the initial idea takes a turn, sometimes remarkably. Trial and error – lots of tries and plenty of errors — are the essential prerequisites. Making art is like that — one attempts to astonish, to have an impact. As difficult as that is, it remains my continuing goal.

I do attempt to achieve veracity in each portrait, avoiding typical “head shots,” but no individual has a single, immutable face. From my experience, everyone can look an infinite number of ways, and there are endless means I can use to bring out these differences in a photographic portrait, whether by using a particular lens, lighting, composition, focus etc., and also in post-production, with the powerful artistic tools of the digital darkroom.

In this Journal entry are four images of 60 Minutes journalist Bill Whitaker, each different from the others, each enigmatic in its own way. It pleases me to discover so many ways of seeing an individual, and for me the ABOVE & BEYOND project provides the wherewithal to pursue this approach.

The distinguished investigative journalist Bill Whitaker came to our studio a few weeks ago. He proved to be relaxed, friendly and accessible. I was interested in how CBS’s 60 Minutes works, and what role Whitaker and his colleagues play in the research, writing and production of the informative segments. (His fellow correspondent, Leslie Stahl, has also come to the studio and will be the subject of this Journal in a few weeks.)

Whitaker was born in 1951 in Philadelphia. He graduated from Hobart College with a B.A. in American history and went on to earn a master’s degree in African American studies at Boston University. In 1978, he also attended a graduate journalism program at the University of California, Berkeley.

Whitaker’s broadcast journalism career began in 1979 at the public station KQED in San Francisco. In 1982 Whitaker became a correspondent for a local television station in Charlotte, NC, then moved to Atlanta, GA where he covered politics from 1985 to 1989. He joined CBS News as a reporter in November 1984, and 20 years later was made correspondent for the CBS news program 60 Minutes. In May 2018, he received the Hillman Prize for Broadcast Journalism.

He now lives in New York City with his wife and children.

What follows is the interview I did with Whitaker before our portrait session.

HS: When did you discover what you wanted to do, and that you had an innate facility for this work?

BW: My first job in television was in San Francisco in public television, KQED, working as a production assistant. I loved being in the news room, I loved the activity, how fast everything was and how you could shoot something at 9:00 in the morning and it was on the air that afternoon.

Then I became a producer. The whole process of setting up a story, meeting people, shooting, writing, putting it together, fascinated me and still does. However, I always wanted to be the reporter, the storyteller.

I searched around for about a year and was hired in Charlotte, North Carolina. After four years I was noticed for my work and was hired by CBS.

A big part of my work is the interview. I talk to people, I want to know what makes them tick, what’s going on inside their heads, why they did what they did. I find people endlessly fascinating.

HS: How do you and 60 Minutes go about finding and researching stories? And how you do an interview?

BW: At 60 Minutes everyone is a journalist; the photographer is a journalist; my assistant is a journalist; anyone can come up with a story idea. It’s usually something we’ve read or heard. Here in New York City you meet lots of people who are doing lots of interesting things, so story ideas come from people you meet. One does preliminary research to find out if it is actually a legitimate 60 Minutes story.

About 25 producers work at the program, all searching for stories and all trying to get them on air; it’s very competitive. The chance that you’ve come up with something totally unique is probably nil, so you do preliminary research just to make sure that it’s really a 60 Minutes story.

Then you go to the front offices and say you’d like to do this story. If they like it they give you thumbs up. Then you and your producers do a serious, deep dive into the story and try to find the people you will interview and the places you’ll go.

We did a story about a police shooting in Tulsa; my producers went to Tulsa and interviewed the police officials, the officer, and the family of the gentleman who was killed. They came back and said there was a good story there. So then we go out with the cameras and at that point I get plugged in.

HS: How do you prepare?

BW: I get a big binder of all the research, all the court documents, all the preliminary interviews that they have done and I study to become an expert on the subject. Then we go out and do the interview on camera. The interview is the basis of the 60 Minutes story, and so interviews are done multiple times, over many days.

HS: Do you ever avoid discomfort? Or do you look for discomfort because that’s where there could be gems?

BW: We don’t avoid discomfort. Someone told me that Mike Wallace said to another correspondent, after she had asked a really uncomfortable question, “Now you’re a 60 Minutes correspondent.”

I think anyone who sits down in front of a 60 Minutes camera – or even me sitting here with you – has agreed to talk and so should be prepared for a little discomfort. I mean, you submit to being questioned.

HS: You deal with some people who are really well-prepared and guarded. Politicians, for instance.

BW: My least favorite interviews. Because they have no problem – and I’m being generous – with spinning the conversation to put them in the best light; their behavior, their decisions, whatever. It’s like genetic; they all know how to do it. They’re difficult to crack.

HS: What about the bias of the interviewer? How does that affect the line of inquiry?

BW: It can’t be possible that your mind is a blank slate. If I’m covering a candidate whose politics are different from mine I bend over backwards to make sure that what I am seeing is what I’m actually seeing, and not what I want to see. I work hard to make sure that I keep my opinion out of what I’m reporting.

This session was a rich experience for me, as these sittings with extraordinary people are proving to be.

Thanks, Bill.

If you have suggestions of other exceptional people we

ought to include in this project, please do let us know.

And if you like these weekly missives, please let others know about them.