At the age of 21, while still a Yale undergraduate, Maya Lin created one of the most extraordinary and moving war monuments, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, DC. Striving to both mourn and ennoble the American dead without celebrating the war, she proposed a simple, eloquently somber black marble wall with the names of the fallen inscribed, column after column. The wall is a eulogy in stone.

In late Fall, 2018, Beverly and I, in a visit to Washington D.C, spent some time at the Memorial.

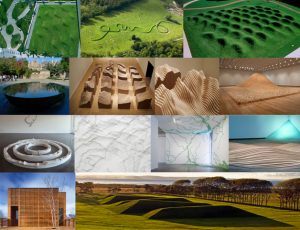

Photographs courtesy of Maya Lin.

Architect, Artist

Lin has a long list of awards and recognitions, including a National Medal of the Arts and a Presidential Medal of Freedom. She is one of the most distinguished of the group of individuals who have come to my studio to be photographed and interviewed for my project Above & Beyond.

HS: I’ve heard you say, “I try to find poetry in my work.”

ML: So much of my work is about observing the natural world. There’s nothing we can do that will ever be as stunningly beautiful as the natural world. I don’t even know if I’m trying to find the poetry. I think sometimes I actually believe you have to let it find you.

My process is almost always to think about a project, think about a site, study it, learn all about it, get an idea of what I might be trying to say and then put it all away. I don’t push it and I generally don’t take on projects that have a deadline. I think there’s a percolation process.

I’ll make a model. I’ll make a sketch. I’ll make a sloppy little something, then I put it all aside. And it’s almost as if all those months of thinking about it, and what happens in the subconscious is why we make what we make but we’re not going to explain it to anyone. Why should we. Can you imagine Jackson Pollock saying, “Well I made this line because of that?” Things just come together. And in a weird way I think the poetry finds me sometimes. There’s magic for me in how I make things.

HS: And don’t artists make things in order to see things that haven’t been seen before?

ML: I want to understand something and I want to touch it and discover what I’m looking at. I don’t know why I make what I make. It gives me incredible pleasure and I think that’s part of it. It just gives me joy.

I think that being an artist for me is very selfish, and that’s good. I also feel at times we can use our art to help get other people to see what we’re seeing which can mean paying closer attention to the natural world. And then there is this kind of activist part of me that says maybe I can reach you in a different way. But I’m still also doing it because I just want to touch it.

HS: Do you ever give up because what you’re seeing is a desert?

ML: There have been a couple of times where I think I jumped too quickly. When you go into your studio as an artist and you make something, you don’t make a blueprint of what you’re going to make. There’s a need to be spontaneous in the making of a work of art at times. If you’re working large scale and you’re working out of doors and you’re working with models and maquettes how close is that maquette to the final form? I like it when I get to manipulate it until I’m actually done with the piece.

I think with the earthworks especially, if I don’t respond to the immediate surroundings in the full scale I’ll lose something. If the final large-scale work looks exactly like the model chances are it almost is dead. It’s flat. So I need to literally bring it to life in the field.

You would get killed in architecture if you did that. You have to draw it up and redraw it. There’s a whole process of getting it bid, having everyone buy in. What you draw up technically should be what you end up building.

HS: Without a deadline how do you know when you’re done?

Are you ever done?

ML: Oh, absolutely. We know when it sings, we know when you can’t do anything more to it or you can’t take anything away from it and it has the right pitch. And it’s pretty frustrating up until that time. And I would assume other artists have the same sort of struggles.

And it’s also the evolution of our voices; what we did in our twenties, what we did in our thirties, what we did in our forties is we absolutely evolve, develop. And I love the fascination of “Oh my God, that’s where this thread went to!” It’s like a treasure hunt in reverse. And I think that’s something that is very much a part of the creative process, that we give ourselves the time to evolve and to change and then you can look back and go, “Oh yes, that was kind of a really young work but it taught me something that led to this.” But you never want to second guess that because that’s where you’re letting your aesthetic voice emerge.

HS: You’ve said that sometimes the process of making something new or creating is magical and childlike.

ML: It’s just that the thought process is non-verbal. It could be happening while you’re asleep. To me the creativity might find me after I’ve had a great night’s sleep or I’ve been struggling with something, you let it rest and then your mind is going to put something together. Is that magic? How we imagine things and how we make things is incredibly magical. But I think others would assume oh the way an architect designs everything has a meaning and a purpose.

HS: It seems diametrically opposed.

ML: Right. And the way artists work, I am not going to tell you why every move is done or I might deliberately break the cadence just because it would be more important to have it not make sense. Because if everything is then logical well it’s almost like a mathematical form and I think you have to break that at times.

HS: The analysis, the science, the problem-solving versus the open-ended anything-is-possible imagination. How do you deal with that?

ML: I have no idea. I think I ended up with both left and right side of the brain tendencies. I think there are different ways people see the world and think and process information. I taught myself COBOL and FORTRAN in high school because I was bored. So I could program and I loved math and I loved logic and science. And then I was always living over in the art school. For some odd reason my brain split between the two.

I felt in my twenties that the worst thing was that I would become schizophrenic; I don’t mean in a clinical sense but just pulled in two directions to the point where the art and the architecture would have almost nothing to do with each other. What I wanted was a wholeness, allowing both sides to be their own creatures.

HS: We’re in a climate crisis. We’re killing off everything.

ML: Including ourselves. I think we’re in the absolute biggest crisis humankind has ever faced and the fascinating thing is we don’t get it. We don’t see it, we don’t comprehend it that way. We have time. The price to mitigate climate change is about $700 billion annually, according to the World Economic Forum; that’s how much we spend on cigarettes every year.

HS: Is our species too successful? Or, ignorant?

ML: I think our species is wired for immediacy like every other species on this planet. We were given the gift that we can write down and understand our history and our past. We have a written record to be able to communicate to future generations. We should be able to learn from our mistakes and we should intellectually evolve. But then we’re so wired for immediate satisfaction we can’t quite comprehend and say, “Okay, I’m going to do without today so that my grandkids are going to have what they need.”

Climate change will make weather patterns unpredictable which will mean food will become an unstable situation. We have thrived over the last 10,000 years because we have lived in relatively stable climates. Once that shifts you’re going to see more disputes. You’re already seeing it. If you thought about climate change as an evil alien attacking from outer space we could see it as an enemy. But it is such a slow boil.

I think we’re in a very critical point.

HS: Is your idea that immediacy, the need for immediate gratification, that we can’t say no to ourselves is a flaw of our human evolution?

ML: It’s a huge flaw. It could be a tragic flaw.