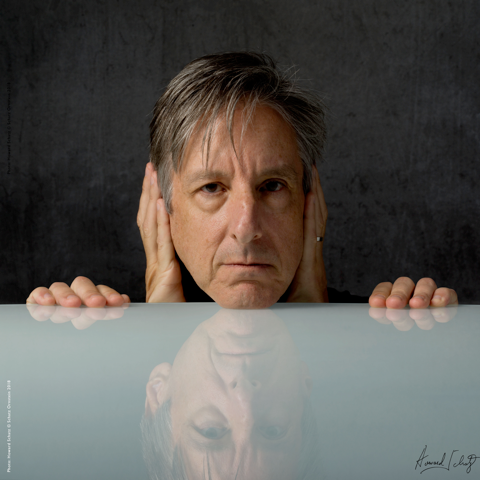

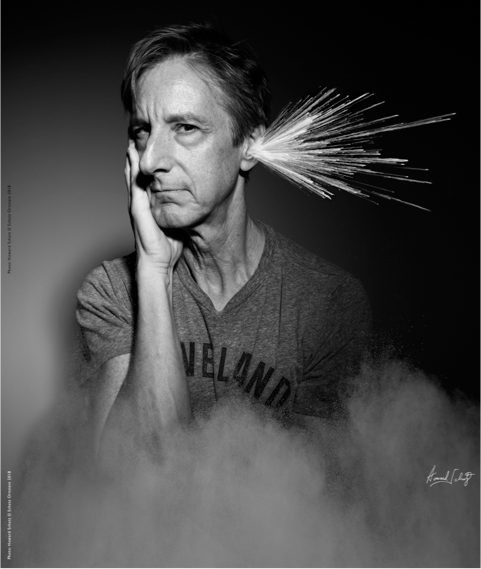

A few weeks ago, the New Yorker Magazine humorist, Andy Borowitz, came

to the studio to partake in my project: “ABOVE and BEYOND; photographic

portraiture and video interviews of extraordinary people in our time.”

Visualizing verbal humor is not easy, but Borowitz turned out to be an amazing portrait and interview subject.

A favorite of New Yorker

readers in print and online, Borowitz is a New York Times-bestselling

author who won the first National Press Club award for humor. He is

known for creating the NBC sitcom, “The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air” and the

satirical column “The Borowitz Report.” In a profile on CBS News Sunday

Morning, he was called “one of the funniest people in America.”

In 1980, Borowitz graduated Magna Cum Laude from Harvard College, where he was president of the Harvard Lampoon Humor Magazine.

In 2011, Library of America chose Borowitz to edit an anthology of

American humor entitled, “The 50 Funniest American Writers.”

Encompassing American humor writing from Mark Twain to The Onion, the

book was released on October 13, 2011, and became a bestseller on the

day of its publication. It reached number eight on Amazon, and became

the number-one humor book in the United States. Both Barnes & Noble

and Amazon named it a Best Book of 2011, and Amazon also named it the

number-one Entertainment Book of the Year.

Since 1999, Borowitz has been the primary host of The Moth, a New York-based storytelling group.

On July 18, 2012, Borowitz announced that The New Yorker had acquired

the Borowitz Report website; the first time that the magazine had ever

made such an acquisition.

Here are excerpts from our interview:

HS: Regarding your process as a humorist and

satirist, is it inspired by reading the news in search for irony, or do

ideas just come to you?

AB: I’m not a news junkie. I’m just aware of

what the few top stories of the day might be. I go to Google News to see

what things are being most widely covered. But I don’t really sit down

at a desk and say, okay, how can I turn this into something?

I just go about my day. I take my daughter to school, I pick her up on

certain days. I make dinner, I go grocery shopping. I exercise. I just

sort of live my life and sooner or later an idea will pop into my head

and I’ll work with it.

If I could turn it into more of a process and more of a science I would

gladly do it, because it would be less nerve wracking. But I don’t need

inspiration. I am a working writer, I do what I do most days a week. It

is a little bit of an anti-process. It relies on a certain amount of

spontaneity.

I am on the whole an improv performer, both live and in writing. I

almost never work at a desk either. I’ll go to the park. I write on my

phone. I’ve figured out a genre of writing that’s so short that I can

write on my phone. That wasn’t the idea behind it. I sort of waited for

that technology to catch up with it.

I’m a runner. So if I’m going for a run around the park, and I have an

idea for a headline, and it’s something very topical, something that’s

happened that day, I sit down on a bench, and start writing.

Maybe half an hour later the piece is done and it’s sent to the New

Yorker, and it’s online in another half hour. The way we’re absorbing or

consuming news, even satirical news, it’s so much of the moment, and

it’s so ephemeral now that in a way winging it and being able to do

something quickly really counts for a lot. Because by tomorrow people

aren’t going to care anymore. They’re onto something else.

HS: Do you care about what your editor does to your piece?

AB: I had one experience which I love, which

was right after Trump was elected. The first few columns I tried to

publish in the New Yorker were really angry. They were reflecting my

mood and I think probably a mood shared by many people who read my

column. But unfortunately the way I expressed it in a lot of these

columns, I was very disdainful, and sort of contemptuous of the people

who had voted for Trump.

And my editor said “You know, we can’t just run all of these pieces

where you’re attacking Trump supporters.” And I asked why not? And he

said, “We don’t want the New Yorker to appear elitist.” And I thought,

well you know, I think once a magazine has decided that its mascot will

wear a top hat and a monocle, I think the ship has kind of sailed…I

thought it was really funny because I have no problem with defining

myself as an elitist. To me, elitism means that I expect and want a

president who’s smarter than I am.

Since the Trump election I’ve actually doubled-down on elitism. I think

it’s a missing element in our cultural conversation that we need to

reintroduce. People are ashamed to be smart and ashamed to be

well-educated. And they’re trying to show that they’re the salt of the

earth.

HS: Can being funny be taught? Can you take somebody who has

never been a comedian and help them become one? Or can you take somebody

who is a comedian and make them better?

AB: I think a funny person can be taught to

write better or to perform better. And like any kind of art form, you

get better with practice and you get better with instruction. I don’t

think if somebody’s just not funny, you can’t…There are all these

comedy classes where they’re like trying to teach you how to be funny,

and I think that’s a huge waste of time.

David Sedaris had a great line I loved, he said, “there’s all this talk

about how tough comedy is and how hard comedy is,” and he said, “comedy

is really hard unless you’re funny.” And that is true. It’s like

anything.

HS: How did you get to this point in your life?

AB: I started in television right out of

college. And partially because my father was a lawyer and worked at the

same job for like 40 years, I thought, and I’m going to be doing this

into my 60s. I’m just going to be going to be going into the office

every day and writing TV scripts. And it never occurred to me that my

life might take different turns. But by the time I’d been writing for

television for about ten years I just thought to myself, is this really

the way I want to spend the rest of my life?

Because to me it was so collaborative, a group of people sitting around a

writer’s room pitching jokes, and pitching ideas. And there’s sometimes

brilliant results from that but I had a very old fashioned view of what

a writer did. And to me a writer was still one person, alone, writing.

And so, after about 15 years I was like, let me just take some time off

and do nothing. And I did for a couple of years, I just didn’t write at

all. I really didn’t have any sort of plan. Then what happened was a

return to my roots which was writing for the Harvard Lampoon, and

writing news satire. And I started writing prose for the New Yorker. I

started up the Borowitz Report in around 2001. And suddenly I felt much

more creative and I was much more fertile than I’d been, say, as a TV

writer.

HS: Do you think writing for the New Yorker is sort of preaching to the choir?

AB: One hundred percent. I think preaching to the choir has tremendous value. I do.

HS: Because?

AB: Because the choir needs to be energized

to make things better. I’m not trying to change a single person’s mind.

Not at all. I just want more people who already agree with me to vote. I

think people underestimate just how difficult it is to change anyone’s

mind.

HS: The Trump voters have not changed their minds, despite all that’s gone on.

AB: They would say the same is true of us, and

that’s fine. My feeling, though, is that if my choir is incapable of

voting, of getting people to register to vote, canvasing in swing

states, writing a check to the ACLU, all those important things that my

choir should be doing, my preaching to the choir actually has tremendous

value because if they laugh, and then their serotonin level momentarily

rises, maybe they’ll write that check. So yes, I am doubling down on

elitism and preaching to the choir. One hundred percent.